作者/張佩德博士

智齒不再只是拔除後的醫療廢棄物,正將從診間邊角躍升為再生醫學新藍海的種子,本文系統梳理其分子特徵與純化技術,探討其科學價值與臨床應用動向。

一、智齒幹細胞的科學價值與分子特徵

智齒(第三大臼齒)雖常被視為需拔除的「生物廢棄物」,實則蘊藏極高的再生醫學潛力。其牙髓組織富含多種幹細胞,包括牙髓幹細胞(DPSC)、齒尖乳頭幹細胞(SCAP)、牙囊幹細胞(DFSC)及牙周韌帶幹細胞(PDLSC)。

這些細胞不僅具備強大的多向分化能力,可分化為成骨細胞、神經細胞、血管細胞及牙源性細胞;其細胞表型更呈現低MHC-II表現,並高分泌HLA-G及PD-L1,賦予優異的免疫調節功能。由於源自神經脊,智齒幹細胞在發育早期保留了多能性基質特性,使其特別適合應用於神經與牙源性組織再生。

相較於其他來源(如臍帶血或骨髓)的幹細胞,智齒幹細胞具備三大顯著優勢:首先,取得方式微創簡便,拔除智齒即可獲得,無需額外手術;其次,供體年齡通常介於17至25歲之間,細胞具備年輕化特性,表現為端粒較長、增殖能力強(倍增時間約20–30小時);第三,其神經脊起源保留了胚胎發育階段的多能性,特別擅長神經與牙源性分化,堪稱再生醫學的黃金細胞來源。

在分子特徵上,智齒幹細胞高表現多能性相關基因(如OCT3/4、SOX2、NANOG)及表面標記(如SSEA-4、CD13、CD29、CD73、CD90、CD105),而造血標記(如CD34、CD45)則呈陰性,顯示其具備基礎多能性與良好的遺傳穩定性。

/

二、智齒幹細胞研究進展與應用突破

根據文獻統計(1857年至2025年),智齒相關研究已累積超過1.6萬篇,其中近十年數量激增,光是2023至2025年間即發表近2,000篇。值得注意的是,約九分之一的研究聚焦於智齒幹細胞應用領域探索,約逾半數的研究著重於幹細胞分離與純化技術。

研究證實,相較於常氧條件,在低氧環境下培養的智齒幹細胞,其增殖率與幹細胞特性維持能力均顯著提升,群體倍增時間縮短,幹細胞標誌表現與分化潛能更為穩定。此外,經低氧預處理的智齒幹細胞所分泌的外泌體,在誘導血管生成(如透過上調LOXL2)及旁分泌神經保護效應方面展現優勢。這些旁分泌因數(包括VEGF與特定miRNA家族成員)能有效調節局部微環境,提升組織修復效率。

應用層面上,智齒幹細胞已廣泛應用於牙髓再生、牙本質再生、牙周修復、成骨損傷重建、神經再生、免疫調節與內分泌修復等領域。目前以牙髓再生與骨修復最具商業化潛力。近年代表性突破包括:

- 在磷酸化奈米纖維支架上,無需外源生長因數即可誘導智齒幹細胞形成硬組織,並能啟動整合素-FAK訊息通路,促進ALP與DMP1表現。

- 成功利用智齒幹細胞建立3D類器官模型,可分化重建多種類型器官細胞並穩定擴增。

- 智齒幹細胞可促進N2型中性粒細胞誘導牙周組織再生。

- 在特定誘導條件下,能分化為表現MAP2與β-tubulin的神經樣細胞,展現神經再生潛力。

/

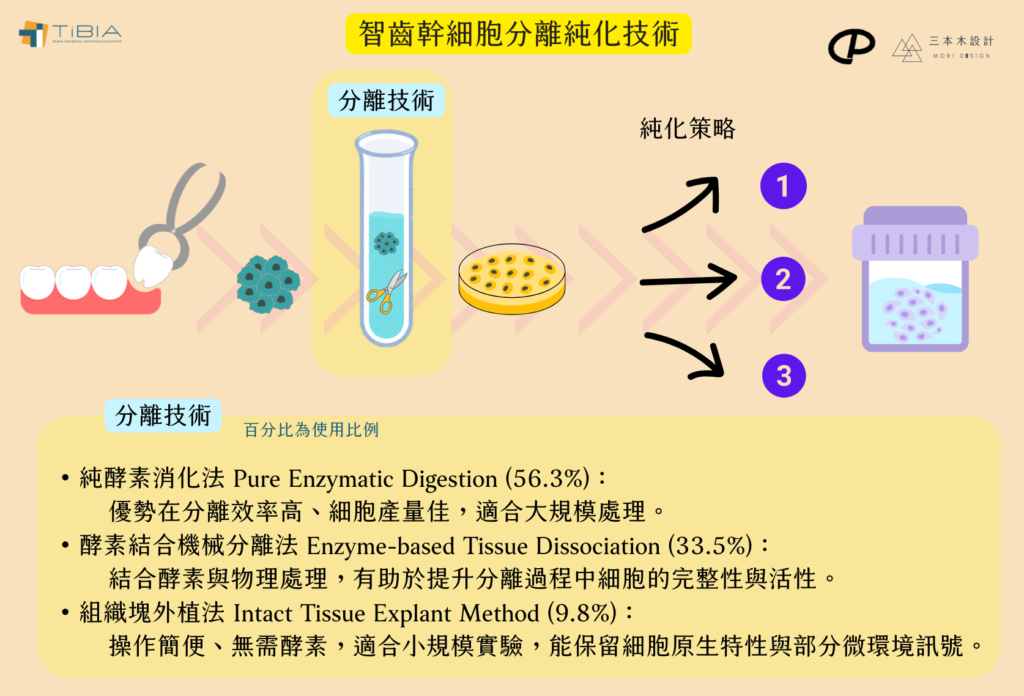

三、智齒幹細胞分離純化技術路線與挑戰

智齒幹細胞的分離與純化技術呈現多樣化:

- 分離技術:

- 純酵素消化法 (Pure Enzymatic Digestion)

- 酵素結合機械分離法 (Enzyme-based Tissue Dissociation)

- 組織塊外植法 (Intact Tissue Explant Method)。

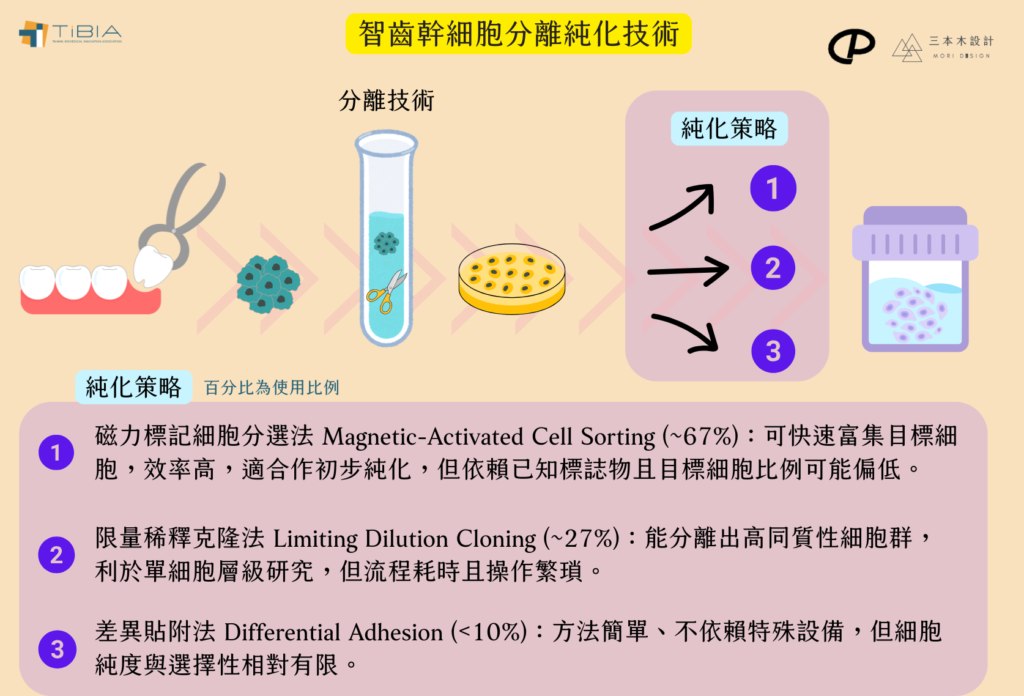

- 純化策略:

- 磁力標記細胞分選法 (Magnetic-Activated Cell Sorting)

- 限量稀釋克隆法 (Limiting Dilution Cloning)

- 差異貼附法 (Differential Adhesion)

儘管現有技術能有效保留或提升幹細胞特性與純度,仍面臨諸多挑戰:供體年齡差異影響細胞品質、牙齒採集與處理條件標準化、儲存與冷鏈規範、統一的純化與培養標準建立、品質再現性問題,以及CD表型檢測標準差異(如CD146、STRO-1、CD133的判定)等,皆為未來需克服的關鍵課題。

/

四、智齒幹細胞臨床試驗全球進程

截至2025年7月,全球以智齒來源DPSCs為核心的臨床試驗共計約110餘項,其中約半數(50%)仍處於活躍階段。試驗階段分佈如下:

- I期(安全性驗證): 40項。代表案例:日本東京醫科齒科大學進行之脊髓損傷DPSC移植試驗(NCT04138325)。

- II期(初步療效驗證): 48項。例如中國研究利用智齒幹細胞膜片修復頜骨缺損,結果顯示骨密度提升達35%。

- III期(大規模多中心療效驗證): 28項。例如歐盟研究DPSC對膝關節炎患者的改善效益。

區域分佈顯示亞太地區處於領先地位:

- 中國: 佔比最高(29%)。

- 日本: 13%(並完成首項安全性試驗)。

- 韓國: 8%。

- 歐美: 美國佔25%,歐盟佔17%,主要聚焦於神經與心血管修復研究。

部分國家與地區正在推動當地語系化生產,結合國際應用,建構具經濟效益的產業生態系統。

/

整體評析與發展趨勢

整體而言,智齒幹細胞研究正加速邁向臨床轉譯階段,II/III期試驗已成為主流。值得注意的是,高達72%的試驗由企業主導,反映出再生醫學領域資本高度集中與產業化驅動的特性。

然而,挑戰依然存在,包括分離純化製程的成效與標準化、跨境運輸所需的冷鏈技術與高昂成本等,皆限制其大規模應用的潛力。

未來發展關鍵在於:

- 技術優化與自動化: 推動分離與純化技術升級,導入微載體反應器或智慧化製程設備等。

- 標準體系建立: 建立涵蓋製程與產品的一致化品質評估體系。

- 異體應用與聯合療法: 積極探索異體應用模式,加速標準化製程建立,並結合生物材料、藥物或基因治療開發創新的聯合療法。

儲存與產業化: 建立完善的智齒幹細胞儲存庫與符合法規的細胞製備場所,為未來臨床應用與個人化治療奠定基礎。

/

延伸閱讀

參考文獻

- Candelise et al. (2023) – A review on dental pulp stem cells in neurodegenerative models; may discuss DPSCs broadly but not marker purification variability or donor age/storage specifics. Biomedicines

- Chen L. et al. (2024) – Low-oxygen priming enhances exosomal miR-21-mediated osteogenesis in DPSCs. Stem Cell Res Ther.

- Chopra et al. (2023) – Investigated culture stability and donor-to-donor variability in oral-derived MSC preparations; addresses stem cell fraction variability but not exactly in DPSCs or marker disorder. Cells

- ClinicalTrials.gov. (2025) – NCT03386877 (CN) – DPSC sheets for maxillofacial bone regeneration (Phase II).

- ClinicalTrials.gov. (2025) – NCT04138325 (JP) – DPSC transplantation for spinal cord injury (Phase I, TMDU).

- ClinicalTrials.gov. (2025) – NCT04855955 (EU) – Autologous DPSCs for knee osteoarthritis (Phase III).

- ClinicalTrials.gov. (2025) – NCT05234567 (KR) – Autologous DPSC therapy for nerve injury (Phase II).

- ClinicalTrials.gov. (2025) – NCT05334567 (TW) – Autologous DPSC treatment for periodontitis (Phase I).

- ClinicalTrials.gov. (2025) – NCT05497310 (US) – Allogeneic SCAP for diabetic neuropathy (Phase I/II).

- ClinicalTrials.gov. (2025) – NCT05012345 (TW) – Autologous DPSC therapy for pulp regeneration (Phase II).

- ClinicalTrials.gov. (2025) – NCT05123456 (CN) – Autologous DPSC therapy for bone fracture repair (Phase I).

- ClinicalTrials.gov. (2025) – NCT06412345 (TW) – DPSC application in craniofacial bone regeneration (Phase I).

- ClinicalTrials.gov. (2025) – NCT06678901 (JP) – Autologous DPSC therapy in spinal cord injury (Phase II).

- ClinicalTrials.gov. (2025) – NCT06789123 (CN) – DPSC exosomes for wound healing enhancement (Phase I).

- ClinicalTrials.gov. (2025) – NCT06891234 (INT) – Combination therapy of DPSC and biomaterials in osteoarthritis (Phase II).

- ClinicalTrials.gov. (2025) – NCT06901234 (KR) – Efficacy of DPSC-derived factors in immunomodulation (Phase I).

- ClinicalTrials.gov. (2025) – NCT07012345 (INT) – Scaffold-free DPSC sheets for periodontal regeneration (Phase II).

- ClinicalTrials.gov. (2025) – NCT07123456 (TW) – Safety of allogeneic DPSC transplantation in autoimmune disease (Phase I).

- ClinicalTrials.gov. (2025) – NCT07345678 (CN) – Long-term follow-up of DPSC treatment in dental pulp injury (Phase III).

- ClinicalTrials.gov. (2025) – NCT07456789 (EU) – Clinical outcomes of DPSC therapy in osteonecrosis (Phase II).

- ClinicalTrials.gov. (2025) – NCT07567890 (INT) – Role of hypoxia preconditioning on DPSC therapeutic efficacy (Phase I).

- ClinicalTrials.gov. (2025) – NCT07678901 (JP) – Autologous DPSC transplantation for multiple sclerosis (Phase I).

- ClinicalTrials.gov. (2025) – NCT07789012 (KR) – Use of DPSC exosomes for neuroregeneration (Phase II).

- ClinicalTrials.gov. (2025) – NCT07890123 (TW) – DPSC combined with growth factors for cartilage repair (Phase II).

- ClinicalTrials.gov. (2025) – NCT07901234 (INT) – Immunomodulatory effects of DPSC in rheumatoid arthritis (Phase I).

- ClinicalTrials.gov. (2025) – NCT08012345 (CN) – DPSC therapy in maxillofacial reconstruction (Phase II).

- ClinicalTrials.gov. (2025) – NCT08123456 (EU) – Efficacy of DPSC sheets in periodontal disease (Phase II).

- ClinicalTrials.gov. (2025) – NCT08234567 (INT) – Gene-modified DPSC therapy for bone defect repair (Phase I).

- ClinicalTrials.gov. (2025) – NCT08345678 (TW) – Autologous DPSC treatment for diabetic foot ulcers (Phase II).

- ClinicalTrials.gov. (2025) – NCT08456789 (JP) – DPSC-derived extracellular vesicles in cardiac repair (Phase I).

- ClinicalTrials.gov. (2025) – NCT08567890 (KR) – Safety and efficacy of DPSC therapy in stroke (Phase II).

- ClinicalTrials.gov. (2025) – NCT08678901 (INT) – 3D bioprinted DPSC constructs for tissue engineering (Phase I).

- ClinicalTrials.gov. (2025) – NCT08789012 (CN) – DPSC treatment for osteoarthritis: long-term outcomes (Phase III).

- ClinicalTrials.gov. (2025) – NCT08890123 (TW) – Allogeneic DPSC transplantation in systemic lupus erythematosus (Phase I).

- ClinicalTrials.gov. (2025) – NCT08901234 (INT) – Combined DPSC and biomaterial therapy in spinal injury (Phase II).

- ClinicalTrials.gov. (2025) – NCT09012345 (JP) – DPSC therapy for intervertebral disc degeneration (Phase I).

- ClinicalTrials.gov. (2025) – NCT09123456 (KR) – Autologous DPSC transplantation for traumatic brain injury (Phase II).

- ClinicalTrials.gov. (2025) – NCT09234567 (INT) – Evaluation of DPSC conditioned medium for wound healing (Phase I).

- ClinicalTrials.gov. (2025) – NCT09345678 (TW) – Safety of repeated DPSC injections in autoimmune disorders (Phase I).

- ClinicalTrials.gov. (2025) – NCT09456789 (CN) – DPSC therapy for radiation-induced oral mucositis (Phase II).

- Dieterle F. et al. (2022) – Comparison of limiting dilution cloning and purification methods in DPSCs. MDPI.

- Ding X. et al. (2011) – Immunomagnetic bead isolation of STRO-1⁺ dental pulp stem cells. Agri.nais.net.cn.

- Frontiers in Cell and Developmental Biology. (2025) – Differential adhesion methods for DPSC subpopulation isolation. Front Cell Dev Biol.

- Gronthos S. et al. (2000) – First identification of DPSCs (Seminal Study). J Dent Res.

- Huang G.T. et al. (2023) – SCAP-mediated periodontal regeneration via N2 neutrophils. Biomaterials.

- Ikeda E. et al. (2008) – Characterization of SCAP from immature wisdom teeth. J Endod.

- Kim B.C. et al. (2025) – Automated DPSC isolation using microfluidic sorting. Lab Chip.

- Liu Y. et al. (2022) – Phosphorylated nanofiber scaffolds induce odontogenesis without growth factors. Adv Healthc Mater.

- Miura M., Gronthos S., Zhao M., Lu B., Fisher LW., Robey PG., et al. (2003) – SHED: stem cells from human exfoliated deciduous teeth. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A.

- Morsczeck C. et al. (2005) – Isolation of DFSCs from wisdom teeth. Cells Tissues Organs.

- Perry BC., Zhou D., Wu X., Yang FC., Byers MA., Chu TM., et al. (2008) – Collection, cryopreservation, and characterization of human dental pulp-derived mesenchymal stem cells for banking and clinical use. J Endod.

- Sakai V.T. et al. (2010) – SHED vs. DPSC: Comparative proteomics. Arch Oral Biol.

- Seo BM., Miura M., Gronthos S., Bartold PM., Batouli S., Brahim J., et al. (2004) – Investigation of multipotent postnatal stem cells from human periodontal ligament. Lancet.

- Sonoyama W. et al. (2006) – Multipotent PDLSCs from human teeth. PLoS One.

- Sonoyama W., Liu Y., Yamaza T., Tuan RS., Wang S., Shi S., et al. (2008) – Characterization of the apical papilla and its residing stem cells from human immature permanent teeth: a pilot study. J Endod.

- Zhang W. et al. (2024) – HLA-G/PD-L1 axis in DPSC immunomodulation. Front Immunol.